| Articles on Tim Hardin |

|

|||

|

Below are three articles published in newspapers and magazines. They are provided here for the benefit of fans. If the holder of the copyright of any article is unhappy with their publication on this website, they need merely e-mail me and I shall remove them. First is a piece that appeared in The Independent in January, 2004, under the banner "Forgotten Heroes" by Bill Kenwright, the London theatre producer and chairman of Everton FC, interviewed by Charlotte Cripps. Who is he? An American folk singer/songwriter with a jazz obsession. His sound was brooding pain and melancholy lyrics that asked endless questions. Born in 1941, he produced an impressive body of work in the late sixties, without ever achieving mainstream success, mainly because he had a serious drug problem. He tried to make a comeback in the early seventies, with the help of Billy Gaff, Rod Stewart’s ex-manager, but Hardin quickly fell back into old habits. He died of a heroin overdose on 29 December 1980. What did he do? He came on to the music scene in the mid sixties as an average blues singer but by the time he had made his 1966 debut, he was writing confessional folk-rock. But sadly, Hardin’s work achieved far greater fame through covers from other singers – Rod Stewart’s version of Reason to Believe or Bobby Darin’s If I Were a Carpenter. Commercially, his success looked more unlikely as his health deteriorated. He did make an appearance at Woodstock 1969, but his albums grew more erratic and weird and sales fell. He did not complete any albums after 1973. Why do I admire him? There are certain people that don’t fit into any category and it is very hard for innovators to survive. But if ever there was a Renaissance Man, it was Tim Hardin. I am surprised more people don’t worship him. He once said, “To know jazz is to know God.” I’m no jazz aficionado, but if you hear his voice – especially on the song Hang On To a Dream, which was my first choice on Desert Island Discs – well, I still think I’ve died and gone to Heaven. Undoubtedly, he was his own worst enemy and by the mid-seventies his creative juices had dried up. But in the mid to late sixties, his music was breathtaking. He was a true romantic, writing simple songs about the promise of love and the disappointment of love.

|

||||

| The following are articles about, or reviews of the tribute CD Reason to Believe - The Songs of Tim Hardin (Various Artists). Uncut (Graeme Thomson): Acclaimed '60s songwriter revisited by Indie fans. Mixing country, folk and jazz, the songs of Tim Hardin have always been well represented by artists far more successful than he ever was, among them Johnny Cash, Paul Weller, Rod Stewart and Robert Plant. Here they're given a further lease of life by less high-profile names. Mark Lanegan offers a faithful Red Balloon, Smoke Fairies a heavy If I Were A Carpenter, and Okkervil River a gorgeous It'll Never Happen Again. Other highlights include The Phoenix Foundation's wintry Don't Make Promises, Snorri Helgason's Misty Roses and the Sand Band's aching Reason To Believe. 7/10. The Independent (Andy Gill): Just as he was, by all accounts, an unpleasant man blessed with enviably beautiful gifts, so do Tim Hardin's songs clothe often unwelcome sentiments in gorgeous melodies. In Red Balloon, for instance, the balloon is not a symbol of childlike joy, but the means by which Hardin transported the heroin he took with Lenny Bruce. Mark Lanegan's darkly knowing interpretation is one of the highlights of this compilation tribute, alongside The Phoenix Foundation's folk-choir version of Don't Make Promises. Most of Hardin's classics are included, though not always treated well: Alela Diane trowels the desolation too liberally over Hang On To A Dream and Smoke Fairies play fast and loose with the lyric to If I Were A Carpenter. **** Mojo (Martin Aston): Sterling tribute to the late, great, troubled troubadour. Given the multitude of Hardin covers down the years, it's extraordinary that this is the first album tribute. This baker's dozen mostly adheres to the Hardin principle: shorn arrangements, nuanced vocals, emotions on a short leash. From Hardin's catalogue of fame, Misty Roses (pensive Icelander Snorri Helgason), How Can We Hang On To A Dream (a woebegone Alela Diane) and Don't Make Promises You Can't Keep (an unusually becalmed Phoenix Foundation) err on the respectful side; balance is restored by an emphatically dark Smoke Fairies doing If I Were A Carpenter. On the one extended jam, Pinknoizu coat I Can't Slow Down in Velvets/Spacemen 3 drone bliss, lending new meaning to Hardin's heroin blues. Talking of which, Mark Lanegan's presence is mandatory here, given his similarly pithy approach to sorrow, but his light reading of Red Balloon is as unexpected as it is enthralling. **** Q (Ian Harrison): Doomed genius' mighty works, covered. The late Tim Hardin - one of the few men in show business to have nodded out on smack onstage at the Albert Hall - bequeathed an outstanding jazz and folk-blending songbook that, over decades, would be covered by, among others, Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash and Paul Weller. Three decades after his terminal OD, this new mob-handed tribute is arranged as if to mirror his grisly decline, the penultimate song being Hannah Peel's take on Lenny's Song, written for fellow heroin user Lenny Bruce, but serving equally well as a wretched self-portrait. Consequently, it's a sombre affair compared to, say Bobby Darin's covers, and with interpretations such as The Sand Band's devastating country rock take on Reason To Believe, it serves as a haunting portrait of an immense talent and a flawed human being. *** Irish Times (Joe Breen): Had Tim Hardin not succumbed to heroin addiction in 1980, he might have just celebrated his 71st birthday. His reputation, revived in recent times by the likes of Okkervil River's Will Sheff, rests on his first two albums, Tim Hardin 1 and 2. These naked songs of hopes and fears were informed by his addiction and by his love for Susan Morss, an affluent actress. A sense of foreboding hangs around every track. The 13 thoughtful readings of the songs, mainly by a mix of British and American new folk acts are testament to the beauty that Hardin managed to carve out of a life of hell. Listen and then check out the originals. *** The Daily Telegraph (Graeme Thomson): Bob Dylan once called him “the greatest songwriter alive” and Joe Strummer regarded him as a “lost genius of music”. Yet when Tim Hardin died in 1980, aged just 39, the world barely raised an eyebrow. His best known songs, If I Were a Carpenter and Reason to Believe, have been covered by a veritable Who’s Who of artists, among them Johnny Cash, Robert Plant, Rod Stewart and Joan Baez. Several more of his songs have been recorded by the likes of Paul Weller, the Byrds and Echo and the Bunnymen. Whatever the era, whatever the genre, Hardin has always somehow connected. Now a new generation of artists is celebrating his music. A tribute album, Reason to Believe: the Songs of Tim Hardin, features British and American indie and alternative rock bands such as Texans Okkervil River – whose entire 2005 album Black Sheep Boy was inspired by the Hardin song of the same name – and gravel-voiced Mark Lanegan. “I’ve always been haunted by his devastating voice and beautiful songs,” says Lanegan. “I can’t imagine anyone hearing him and not feeling the same.” Born in Eugene, Oregon, in 1941, he arrived in New York aged 20, after a spell in the Marines, to study at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. Already in thrall to heroin addiction, he gravitated towards the thriving Greenwich Village folk scene, befriending and playing with Everybody’s Talkin’ composer Fred Neil, Mama Cass, Karen Dalton and future Lovin’ Spoonful leader John Sebastian. What set him apart from his contemporaries was a rich, artful voice and a fistful of songs that hinted at despair, drug abuse and a bruised romantic sensibility. His first two albums, Tim Hardin 1 (1966) and Tim Hardin 2 (1967), come close to perfection, and still provide the most persuasive evidence of his finely wrought songcraft. Their highlights range from the bluesy Red Balloon to the countrified Reason to Believe, and the cool, clicking jazz-pop of Misty Roses. Though fleshed out with strings, bass, harmonica and keyboards, the elegant arrangements convey a timeless, unhurried classicism. “There is something very disarming about how simple those songs are,” says Will Sheff of Okkervil River. “A Tim Hardin song never outstays its welcome – it’s very short and pretty: one verse, one chorus, second verse, the song is over and he’s out of there. It’s like a tiny, perfectly cut gem.” Black Sheep Boy – a beautifully opaque song about family and drug addiction – says all it has to say in under two minutes. “You get what he’s telling you without him spelling it out,” says the Canadian singer-songwriter Ron Sexsmith. “When it came time to make my first record I can remember keeping that in mind.” With such obvious gifts, why did Hardin never quite make it as a solo artist? Unreliable, untrustworthy and unsettled in his own skin, he was, says Sexsmith, “very troubled and couldn’t really play the game – or wouldn’t”. His live performances were erratic. Then there’s that jazz-inflected voice, with its ostentatious waver which, even now, divides listeners. “He used lots of vibrato and that was not in style at the time,” says Sheff. “Flat, artless singing was the popular thing, whereas he had a very beautiful voice. I think with Antony Hegarty, Rufus Wainwright and Justin Vernon, that kind of voice is much more palatable now than it was then.” In 1969 Hardin signed to Columbia Records and enjoyed a minor hit single with Simple Song of Freedom. He played at Woodstock – you can see him in the movie footage, a little belligerent and very obviously out of it – and the same year released the experimental Suite for Susan Moore, prima facie evidence that the cool precision of his writing had begun to unravel. “Later on he got less concise and it didn’t work so well,” says Ian McCulloch, frontman of Echo & the Bunnymen. “It became directionless, and I think a big part of that was drugs.” Hardin spent much of the Seventies in turmoil. His final album, Nine, was released in 1973. Shortly after he dropped off the radar completely before resurfacing, in LA in 1979, to make some new recordings and sporadic live appearances. He died of a heroin overdose on December 29 1980. “Stories like Nick Drake trick us into thinking that that kind of posthumous rediscovery is going to happen to everybody who is good,” says Sheff. “In fact, it doesn’t. Mostly the world doesn’t really care, but Tim was more than an interesting artefact of the Sixties. He has staying power. The songs will live forever because they’re so good that people will always cover the best of them. They are for all time.” | ||||

|

This next article appeared on the Trieste Magazine website, from whose archive I've lifted it. A Reason to Believe in Tim Hardin: Ian Sharrock reflects on his memories and recounts the sad story of Tim Hardin's life It was the fag end of the summer of '66 when a sharp-suited singer walked onto my TV screen and sang "If I Were A Carpenter". I just couldn't believe that Bobby Darin, hitherto famous for songs such as "Mack The Knife" and "Multiplication", was singing what I presumed to be a beautifully arranged traditional folk song, in the same vein as "The Raggle Taggle Gypsy" or "Black Jack Davey". I set out the following day in search of the album, which I found in a local record shop, then dashed home to persuade my mother to go into the shop on my behalf - I just couldn't bear to be seen buying a Bobby Darin record. The album was a real gem - the track listing boasting several Tim Hardin songs (a name I hadn't previously heard). Each of the songs was a mini-masterpiece. I don't think any of the songs lasted more than two and a half minutes, but that was it, I was hooked. Tim Hardin was born in Eugene, Oregon on December 23rd 1941. His parents Molly and Hal had both been musicians: his mother had once had a career in classical music, his father at one time played bass. Tim spent a great deal of time during his formative years under the strict supervision of his maternal grandmother who went by the wonderful name of Manner Small. Tim had known from the outset that he wasn't like the rest of the boys in the small lumber town. He wanted to act and to sing. When he eventually left Eugene, it was to join the Marines, not one would say, the most direct route to an acting or singing career. He was shipped out east and came back, like many of his fellow soldiers nursing a deadly heroin habit. Leaving the Marines in 1961 he returned briefly to Eugene, before moving to Greenwich Village, where he was enrolled at the rather grand sounding American Academy of Dramatic Art. In the village he met Karen Dalton (who is curiously in the position of gaining posthumous fame through the re-release of her second album It's So Hard To Tell Who's Going To Love You The Best on Megaphone) and Richard Tucker, and it was almost certainly their influence that encouraged him to think more seriously about his music. He was dismissed from the Academy after skipping too many classes, and re-merged in Boston around 1963, where he received a call from Erik Jacobsen, a one-time banjo-playing folkie (and more recently producer of Chris Isaak). Jacobsen invited Tim down to New York to work on some songs. Tim moved back to Greenwich Village in 1964 and through Jacobsen, he gained an audition at Columbia Records. He was still on heroin and heavily into marijuana, and the resulting sessions were a nightmare. Columbia passed on him, But Jacobsen's faith was unshaken. Eventually, Tim was placed with the partnership of Koppelman and Don Rubin, who were at that time working jointly on the Lovin' Spoonful. They found a home for Tim on the Verve-Forecast label, a division of MGM and Tim's first single, "How Can We Hang On To A Dream?" was issued in February 1966. His first album Tim Hardin 1 was released in the summer of 1966, by which time he had married Susan Moehr - who was to be his muse for some of his finest love songs. None of Tim's albums sold well. He had a cult following that probably accounted for sales of between ten and fifty thousand per album. Even so the first album and its innovatively named follow-up, Tim Hardin 2, were two of the best albums of the 60s, influencing many artists, from those who covered his songs, Johnny Cash, The Small Faces, Waylon Jennings, Scott Walker and Bobby Darin (who threw away his toupee) to those artists such as Nick Drake, Astral Weeks-period Van Morrison, and latterly Ron Sexsmith who were influenced by him. When Ron Sexsmith was asked by his record producer to give some kind of reference as to how he wanted his debut album to sound like he told him to listen to the first two Tim Hardin albums. In 1969 Hardin arrived in England to take what was then known as the "sleep cure" for heroin addiction. This involved the use of barbiturates to get over the initial withdrawal stage from heroin, sadly, Tim emerged from the "cure" addicted to barbiturates. Back once more in the States, Tim was living in Woodstock, where he recorded a highly personal and confessional Suite for Susan Moore and Damion - We Are-One, One, All In One. There were no songs on this album for Bobby Darin to cover, but, in a strange reversal of fate, Tim covered Darin's "Simple Song Of Freedom" and it gave him his only "Hot 100" hit. Shortly after, his life in Woodstock took a downward turn when Susan left him. He then recorded his second album for Columbia: Bird On A Wire. Although there were few self-penned songs, for me, this was his finest moment. He makes Leonard Cohen's much-covered "Bird On A Wire" his own, with an impassioned vocal performance, and the entry of the choir just before the end, although potentially tacky, is one of his greatest moments on record. Hardin's version of the traditional song "Moonshiner" matches even Dylan's version and standards such as "Georgia On My Mind" are sang with real feeling in his voice. The strands of his varied life and musical influences, plus his fine vocal technique all come together and, with the sympathetic backing of jazz luminaries, like Joe Zawinul, the tracks were imbued with the depth of sweet melancholy that I had never before experienced. It was rather like pressing your tongue to a bad tooth - both painful, yet irresistible. Tim, still in Woodstock, felt trapped. He had lost his driving licence and even though he had given up heroin again, he was drinking heavily, and like most alcoholics and substance abusers, Tim lost touch with his feelings, and hence his songs. He made one last record for Columbia Painted Head, which although a good workman-like album did not contain one original song. Tim left Woodstock and went to England again, where as a registered addict, he could receive his heroin on the National Health. Whilst in London he and Susan had a brief reconciliation, but he lost her again and lost his songs too, by signing away the copyrights. Returning to the USA he stayed in Seattle and then moved to Los Angeles to be close to his son, Damion. By this time, Tim cut a different figure, bald and overweight, almost unrecognisable, even to his old friends. He was on a downward spiral, hurting those close to him and back on heroin (he had been clean in Seattle). During his last troubled months Tim worked once again with Don Rubin. They had two tracks ready for an album, but Tim Hardin died in Los Angeles on December 29th 1980. When the County Coroner's Office handed down its verdict, his death was "due to acute heroin/morphine intoxication". |

||||

|

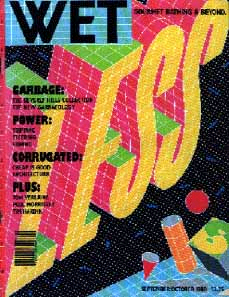

The final article was published in a little-known Los Angeles magazine, WET, that existed in the late seventies and early eighties, but is now defunct. The article consisted of an interview with Tim, published in September 1980, four months before his death. It was conducted by Ann Louise Bardach. I have edited the article somewhat - primarily to remove the profanities (of which there were many). Please bear in mind, when reading this interview, that he was not well and his views on events in his past were largely perceptions coloured by his drug intake. I am aware that some of the content is quite upsetting to Susan Hardin, to whom I passed a copy before putting it on the website. Nevertheless, she kindly gave me permission to make it available to website readers. |

|

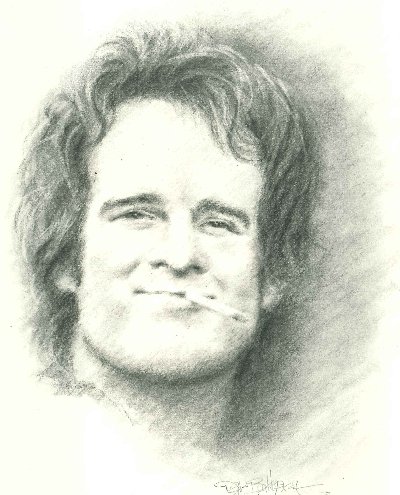

|||

The Heavy Heart of Tim HardinAn Interview by Ann Louise BardachBefore there was Bob Dylan, there was Tim Hardin. "He was the greatest," recalls a fan. "When I left home in '66, I knew every Tim Hardin song word for word. Everybody did." Indeed, there were a few years in the '60s when Tim Hardin turned out hits (Misty Roses, If I Were a Carpenter, Reason to Believe, Long Time Smuggling Man, etc.) with the speed and aim of a Gatling gun on remote. It wasn't just a repertoire of songs that went 'gold' or 'platinum', it was songs with indisputable claim as classics. Quite simply, Time Hardin is the stuff of legends. Like Piaf, his personal tragedy was as well known as his songs. Music mags in the '60s chronicled his drug addiction, busts, shattered romances, and endless litigation over the millions of dollars of royalties earned by his songs. Music industry insiders speculate that Tim Hardin's songs have been recorded by more artists than any other songwriter of the '60s (e.g. Frank Sinatra, Rod Stewart, Joan Baez, Marianne Faithful, and Bob Singer, to mention a token few), yet Tim Hardin is broke. It's always been that way. An endless series of lawyers, agents, managers and record companies adept at labyrinthine contracts have kept Hardin on his knees begging for his dinner for more than a decade. Some will coolly cite Hardin's legendary heroin habit as the source of his poverty. Yes, to some degree - though many allegedly drug-addicted musicians live comfortably, if not luxuriously (Keith Richards takes a limo to his beach house in the Hamptons). It's been almost 20 years since Hardin's heyday. For the last few years he has lived quietly with his companion Janet in a small West Hollywood apartment in the rear of a shingled cottage. Some half dozen gold and platinum records are on the wall, hung as indifferently as potholders. It is a tidy, clean place, with no frills - its furnishings are strictly utilitarian. By all reports, Hardin is "Clean, healthy and trying to trim his waistline." And he's just finished writing an album of new songs, which he is currently recording. Ann Louise Bardach: Let's start with the album, Tim Hardin I. Legend has it that Dylan once said you were the greatest song writer of our time when that album came out. Tim Hardin: Yea, I played him part of the album one night and he started flipping out, you know... How? Man, he got down on his knees in front of me and said: Don't change your singing style and don't bleep 'a' blop... When did you first meet Dylan? Was it before Tim Hardin I? I met him when he was taking bennies and coming by saying, "I wrote a new tune, I wrote a new tune." What year was that? '62, '61. When did you break with Dylan? We never got together. He's a cold man. He was thinking, he was listening to what everybody said all the time and going, "Umhum, yup," and writing it down in his little photographic memory, you know what I mean? Taking pictures of everything and reproducing the whole lick for himself. Then he learned to give somebody else a little credit, by having their picture on the album or something. Did you ever play with him? Yeah. And Jesus. (laughs) When did you make your first album? I made This is Tim Hardin in 1961 and then it came out in 1967. The guy in the studio sold it to Ahmet Ertegun. Did you have any problems? What do you mean? Problems about collecting dough? (loud laughter) Aw, hey. I never got any money off him. Did Tim Hardin I go gold? There's not a record I've made that didn't. Four albums? Thirteen. Albums? Yeah. Two of them were anthologies so we're really talking about eleven, and two of them were repeats of other stuff, so we're talking about nine. But as far as releases go, it's 13. Right now, I'm so down and disconcerted, you know. People always wanted a piece of me, a piece of my songs. I don't have no protection, no contracts. I just talked to Johan Vigoda (rock star lawyer) the other night and I told him what happened. He flipped out. We were sitting in front of The Troubadour, Johan, who's a multimillionaire, is sitting there chewing on his own matchbook going "Tim, that's not legal. They couldn't have done that to you." . But they did it to me and it is legal. What did you talk to him about? I told him how I don't own any of the songs. When did you start using junk? I started using junk when I was sixteen. How old are you now? Thirty-seven. I've stopped. Really? Yeah, except for when I can't. That's some way of stopping. You look clean. I am clean. And you've put on the traditional clean-up tummy. The traditional fifty pounds. You started using junk when you were sixteen? In high school, playing football in Eugene, Oregon. How did you get junk in Eugene, Oregon? In a drugstore. You mean you bought morphine? No. I stole it. You stole heroin, pharmaceutical heroin? Dailudin, Pantathon, morphine. But how did you know about it...? I read about it. I was going out with a girl whose old man was a doctor and I got into his PDR [Physicians Desk Reference]. I like to read. I got a broken collar bone playing football so I went, "Hey, I can go right over to the Rexall. I know my way in." I lifted the safe, the whole thing. Because you had a bad shoulder or because you had some pain between the ears? No. Physical pain. I never even thought about stopping. First time I got off on smack I said, out loud, "Why can't I feel like this all the time?" So I proceeded to feel like that all the time. Did you finish high school? No. I went into the Marine Corps. What year was this? '59 is when I went in. So you were in Korea. No, no. We were busy startin' Vietnam. Were you using dope while you were in the Marine Corps? Oh, yeah. How did you get it? Corps men, Navy corps men. Spelled c-o-r-p-s-e men. How did they get it for you? They had a key. To the medical safe? Yeah. When did you start playing guitar? I got back from the Marines and my high school drama coach, who's a heavy named Ed Racazino. Mr Racazino. I still call him Mr Racazino. I can't call him Ed. You know what I mean? He sent a letter to the American Academy of Dramatic Arts and I go over to New York. I got a scholarship behind an audition that I just made up. You learned how to play the guitar at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts? No. I left there after about six weeks. I went in there one day and the subway had goofed and I was late and I was rushing to class. They stopped me at the damn office. "Just a minute," and they gave me a pink slip for being late. So I go, "Aw, heck, not high school again." I had two twenty dollar travellers cheques left and I bought a Harmony nylon string guitar that cost exactly forty dollars. The guy saw that's what I had. I couldn't even afford a guitar book to learn chords with. I figured out some chords on my own and wrote a few tunes to fit what I knew on the guitar. What year did you meet your wife, Susan? '64...'65. I'm not good on dates. Susan came by to see the guy who was taking care of my pad, raking leaves and sweeping out the house, you know. She was the main star of The Young Marrieds, a soap opera which was the highest rated show on TV then, including prime time, and so she comes to the door. I'd never seen her before. She's good looking, you know. I said, "John's not here" and took her right back out the door. We went down and got a hamburger or something and went over to her pad and got it together. It was great.... We ended up at her house eating hamburgers, you know. We also ended up eating each other. You know what I mean? I dug her pad. She had dough on her and everything.... Then Susan comes up and moves into my pad, but this guy, Archie, a hit man I copped from all the time in New York shows up all of a sudden. Why was Archie there? He was a hit man? Yeah, but he's also a friend of mine and he decided to take over the pad, you know, because I owed him a couple of bucks. One night Archie says, "Listen, man, lend me your car. I got to cop." And I says, "No, man, I can't lend you Susan's car because that's the only car around." In the morning Susan and I wake up and we go into the kitchen and we look out at the damn place where the car is supposed to be. We look out and the car isn't there. Then we realize, "Heck, man, the keys are gone." About ten minutes later there was this terrible shriek, a shriek of car and tyres, and sca-plow right into the house across the street, right through the living room window. That was Archie who had stolen the car and was rushing back in desperation because he couldn't find the dough he's taken to cop with. I said, "Archie, don't come back in here. I got a .44 magnum." I gave the gun to Susan and ran down the street to distract his attention. He ran after me. He was going to kill me. He could have done me so easy, but I could run. I was down on the corner by a liquor store when the cops came and I said, "He-ulp." Archie ran over my foot and tripped and the cops jumped out and got all of us. Did you have dope on you? Boy, did I ever. There was an ounce in the brick wall outside the house. They busted you and Susan? The cops goofed because they didn't have a search warrant or nothing. It got thrown out of court. Where did Susan's father [Judge Morris] come in? Susans' father was a judge. He was called while we were both in jail. I goofed on Archie. I told on him. I couldn't help it. I had to. So what happened to him? Archie got sent back to New York. And you had been married for how long? We weren't married until two weeks before Susan left me. Your son Damian was already born when all of this happened? I was holding Damian in my arms at the wedding. So you were with Susan two years before you got married? Call it five. She said, "Let's get married," made up little matchbooks and little mementos and everything. We had fifteen neat people come by and all. I wrote the ceremony myself. The Justice of the Peace was crying it was so beautiful. And then two weeks later she was off. Yup. The two of you have never gotten it back together? No. She asked me. She said, "Tim, please." I said, "I can't make love to you anymore. You can't make love to someone you really, you really basically hate." It's rough for a non-junkie to live with a junkie. But I was cool. I had gone on a methadone program. Everything was okay, man.... Well, I hit her a couple of times. You hit her when you were angry? It's a killer crime. People ought to be hung for it. It's a bad thing. Guys can kill girls easy. And it kills me that I did it, it just kills me (sobs. Five minute interruption.) I never lied to her. She taught me how to lie because her disapproval was so heavy. I couldn't stand it, you know, the dumb peasant. I don't mean peasant. I can't even think of the word. She made me feel bad. There was a class thing there? Which was part of the reason I loved her so much. I married a girl on the hill. But I'm smarter than she is. She dug that. Do you see Damion? Yeah. That's his school right over there. He's had his father all the time. You're about the only musician alive right now who isn't a born-again Christian. Why do you think they're all into that? Because they might die someday or something. I don't mind. I can watch people die. I've seen them. I've seen people croak and I've thrown them out the window. "Aw hey, man, Manny just died. What are we going to do with Manny?" Out the window because you don't want the body in the pad. You might get busted anyway for what you're doing already. Busted for murder? Who wants that? Why did you stop using junk? It got so inconvenient and I got broke. Are you in a methadone program now? Nope. I was on methadone for seven years. It's the hardest work there is. I kicked methadone, speed and valium. That's how come I look fat. It's been two years now. I'm in perfect shape except for being overweight. You look twenty pounds over and that's it. Try fifty. You didn't ever see me at 140. I weight 190 pounds now. Do you believe a guy 5'6½" that weighs 190 pounds and can still move? This interview was published in September, 1980 and Tim died in December, 1980. |

||||

| Top Page | Biography | Photographs | ||

| Record Listings | Record Sellers/Values | Top Ten Tracks | ||

| In Concert | Your Comments Blog | Acknowledgements | ||

| Webmaster | Link to related sites | My Home Page | ||